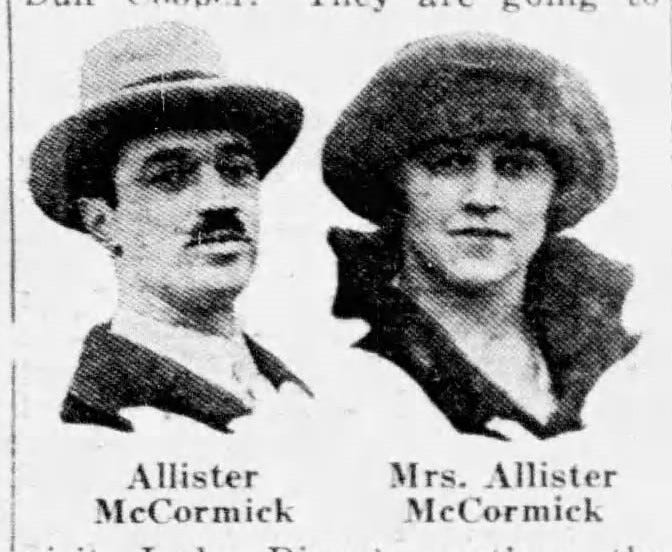

In early July 1922, Mary Landon Baker settled upon a new date for her wedding to Allister McCormick: August 17—a day that would come and go with shockingly little notice, though a blurb in the Journal Gazette announced on August 19, with some naïve hope, that local reports declared the couple had married.1 A week later, Mary issued a telephone statement from Scotland regarding her intention to wed within a matter of days.2 By September 16, wire services reported yet another cancellation in the “romance […] which has set a new record for marriage postponements,” with Mary making hasty plans to depart London for Switzerland on the heels of announcing a new date of October 20.3 And later that day, the Cosmopolitan News Service found itself obliged to report on Mary’s sudden cancellation of said travel plans, the tone underscoring their own exhaustion with the narrative:

It is not known at present when the marriage will take place. It has been postponed half a dozen times already, owing to the temperamental views of Miss Baker.4

Should the story have been expected to conclude with the same dramatic flair with which it began? In December 1922, the final romantic break came the way all late reports had: in limited column space, presented with the verbal equivalent of an eyeroll.

Mary Landon Baker of Chicago, who left Allister McCormick waiting at the church last New Year’s Day [sic] and who since has been gallivanting around throughout Europe every now and then just one jump ahead of matrimony—according to cabled reports—is coming home. Her mama’s going to bring her back.

Bringing the affair almost full circle, Alfred Baker, Mary’s father, contributed his first on-record comments since that ill-fated day: “My daughter is returning as she departed—unmarried,” he said. “And with no matrimonial plans of which I am aware.”5

In early January, a report on a new suitor emerged from the ether: Morris Volck, “son of the wife of the Brazilian ambassador to England.” Maybe Alfred Baker could shed some light now?

“Volck!” Baker exploded when he heard about it. “How do I know? I never heard of the name or anything like it, but that might not mean anything.”

This outburst led into a subsection sarcastically titled “‘Dad’ Doesn’t Know Anything.”

Baker reiterated his ignorance of Mary and Allister’s drama. “But I do wish the world would quit being so curious about the love affairs of Mary, or if they have to keep on with the curiosity, to stop asking me about it; I don’t know.”

His frustration quickly morphed into a decent facsimile of a Radiohead song:

“No, I won’t hear later.

No, I don’t know when she’s coming back.

I don’t expect to know until I see her here.

No, there won’t be any use of calling me later.

Good-by.”6

But when caught in Paris that January, confronted by another band of reporters seeking to know when, if at all, she truly planned to wed Allister, contrary Mary—the procrastinator, the lingering aesthetic—somehow, finally, found her resolve.

“I am not going to get married at all,” said Miss Baker. “Not to Allister or anybody. Never. I’m going to be an old maid.”

The newspaper men, who really hadn’t expected any reply at all, or at best, a sort of half-hearted “perhaps,” were stunned by this sudden decision.7

This was, of course, another misdirect from Miss Baker.

The rest of that month ushered in more wire reports on Mary’s social life, “the little American’s being crowned queen of the smart night clubs and cafes.” But February 1923 saw a new development in the Mary lore. As documented in one of the more colorful entries in the Baker/McCormick literary canon, she returned from ten months overseas with both a “thick as fog” London accent and a new boyfriend—actually making good on the threat of replacing Allister with an Englishman.

Mary and her beau—Geoffrey Algernon Cunard, a scion of the freight business and “candidate for the enviable role of perennial waiter-at-the-church”—scrapped with newspapermen.

“Are you the goil that didn’t show up at her wedding?” one eight-minute member of the Fourth Estate said carelessly.

“Rawther!” the new Mary said with a drawl that fairly shrieked of London.

After delivering a lengthy and impassioned refusal to answer any further questions, Mary answered some questions.

“The engagement’s off. It really is. I mean to say I’m not going to marry Allister McCormick, and that’s quite final. I mean to say there’s really nothing else to say about it. It’s no good talking of it anymore.”

In a dramatic turn, Mary’s mother provided her first on-the-record commentary of this affair, asking a sadly prescient and, frankly, meta question: “The engagement is broken—must this ill-advised mistake of her youth haunt her the rest of her life?” Poor Geoffrey, nearly in tears, subsequently refused to declare his marital intentions with regard to “the erstwhile champion of procrastination.”8

By April, those intentions—and Mary’s—were so boring as to be noteworthy. “Mary Landon Baker’s flair for thrills and sensations is past,” opened a seemingly random update. Promised Mary’s older sister Isabelle, AKA Mrs. Robert M. Curtis, Mary would slip into ordinary life, “never again to jilt anybody at the altar, elope with a British peer or do anything else to make her internationally famous.”

Lest one assume that Mary or Mrs. Curtis issued this press release independently to drum up media interest, an odd detail suggests it’s more likely that someone pulled an Alice Langellier:

“There isn’t going to be any more written about Mary because she isn’t going to do anything to write about,” Mrs. Curtis said. She added that Mary was still asleep and should not be disturbed.9

The press was bored and by mid-1923, had yet to find a suitable society successor. So in May, a writer with the pen name “Debutante” set out to divulge the reasons for Mary’s myriad jiltings of Allister. This deeply researched investigation into “California heiress” Mary reassigned the infamous Fourth Presbyterian postponement of January 1922 to May 1921, but provided a final firm explanation of the previous year’s rollercoaster: “Mary was the victim of a hopeless love.”

Debutante proceeded to rehash the Barry Baxter narrative, though introduced a new character in performer Teddie Gerard, “London’s popular terpsichorean idol,” a rival to Mary for matrimonial misadventure, and Baxter’s own true love—despite Gerard’s involvement with parties including “E.R. Thomas, whose wife named Miss Gerard in her divorce suit; George Bronson Howard, brilliant novelist, who committed suicide for love of her, and Prince Dimitri Pavlovitch, a Russian.” Not mentioned in Debutante’s piece, but entirely likely, is that Baxter and Gerard may simply have bonded over a mutual love of chows.

The article also served as a sort of rehabilitation piece for Mary:

Psychologists have attempted to explain her action on grounds of anesthesia to love, and in other ways.

The true reason lay in the fact that Mary cherished in her heart memories of a greater love—a love against which she struggled—an affection that never was requited, and now never can be.10

While the press continued to seek new opportunities to work “pull a Mary Landon Baker” into a story, the lovelorn Allister moved on with his life. In late August came the rumblings of an imminent engagement to London native Joan Tyndale Stevens, daughter of actress Vera Tyndale. The prediction was borne out three days later, shared via the wires and announced in at least one paper with an incredibly rude write-up.

“Who’ll take the place of Mary?”

The Chicago gold coast sang this song Tuesday in place of its old and time worn question: “Will Mary Landon Baker ever marry McCormick?”

Mary kept Allister McCormick waiting at the church on three separate occasions, when they were supposed to have been married and on her recent return from Europe announced the match was all off. Now the cables say Allister is engaged to a Miss Joan Stevens of London, and nobody can be found in all the city’s broad confines who knows who Miss Stevens is.11

The engagement also inspired a spate of retreads of Debutante’s bombshell Mary and Barry Baxter story, this time framed by Allister’s new engagement.

Befitting Allister’s role of bridegroom in perpetuity, he and Joan would have two wedding ceremonies—a civil one in Paris on October 5, and a religious ceremony at the British Embassy two days later. The first began with a psychological scare for Allister and Joan alike:

The entire party entered the marriage hall a few minutes before 11 o’clock, but Deputy Mayor Chamonnet, who was scheduled to officiate, was several minutes late, and the bridegroom, growing restless at the delay, had left the room when the bride came in. She glanced nervously about as the ushers paged “Monsieur McCormick!” through the reverberating corridors of the City Hall.

Happily, both Allister and the deputy mayor would reappear, the latter pleased to dedicate a romantic speech to the couple:

“I am very happy to unite in wedlock a member of one of the best English families—our dear allies the English, in spite of what people would lead the world to believe—to the representative of the great McCormick family of America which proved by sending 25 of its members into the firing line its great love of our country and of justice.”12

Strangely, this news came in conjunction with quite an update on the ex: Mary’s rumored engagement, revealed on October 5 by the Chicago Tribune and bundled in some papers13 with the report of Allister’s wedding, to Bojidar Pouritch, the 35-year-old consul general of Yugoslavia.14 But Mary’s friends, noted the Tribune, denied the engagement.

Small wonder that by June 1924, readers would be treated to stories like “Mrs. Allister McCormick Tired Of Mary Baker Talk,” which spotlighted the newlyweds’ trip abroad and concluded with this spectacular and not unreasonable quote from the bride:

Mrs. McCormick, listening to her husband talking, remarked: “I am sick and tired of hearing of Mary Langdon [sic? shade?] Baker. Wherever we go in this or any other country we are asked, Where is Mary Baker? It is becoming disgusting to me and bores me horribly.”15

Another rendition of the story, with a slightly different though identically furious version of Joan’s remarks, described her as “almost purple with rage” and blamed the incident on a remarkably unfortunate coincidence:

The couple would not have been discovered had it not been that McCormick dropped a $1 bill. Reporters ran to pick it up, and handing it to the Chicago millionaire recognized Allister. He admitted his identity.16

Anyone still asking the McCormicks about Mary’s whereabouts wasn’t following the society pages very closely at all, where her past would swiftly prove prologue. American readers in November 1925 would be treated to the headline “Twice Truant Bride of McCormick Subject for Wedding Rumor Again.” The lucky fellow this time was 48-year-old Captain Ralph Peto, “divorced two years ago by a cousin of the Duchess of Rutland.” The sourcing on this news was questionable; “[Mary] did not mention any engagement and relatives here could not be reached.”17

This was the last any Mary devotee would hear of Peto. Two months later, in an International News Service piece with the unproofread but alliterative headline “Mary Landon Baker Nenies Nuptial Aims,” Mary would make sure to throw out some fresh chum on her way to a stay with the Duchess of Leeds. “’Reports that I am engaged or about to become engaged to the Marquis of Carmarthen’”—the Duchess’s son, presumably John Osborne—“‘are just newspaper talk,’” said Miss Baker today. ‘I am engaged to no one.’”18

For now, at least.

In August, the Associated Press inexplicably returned to the senior Baker for insight. She would not, confirmed Mary’s father, be wedding Lord Carmarthen. But if she had plans to marry anyone else—like Bojidar Pouritch, making a surprise reappearance like an early fan favorite during season 4 sweeps—Baker was equally clueless.

“Mr. Pouritch has been devoted to Mary, but I imagine the rumor of an engagement became current because he has gone to London from Belgrade, where he is now living, to see Mary.”

Mary will marry when she is really in love and not before, Mr. Baker added.19

But the rumors persisted into October, meriting a standalone report datelined Belgrade. “Mary Landon Baker [...] today is reported to be contemplating matrimony again,” it began, before briefly explaining the three-year-long rivalry between Pouritch and Carmarthen for Mary’s affections, in which Pouritch had gained the upper hand. Why trust in rumor this time? Because Mary, the report concluded, had actually made her way to Belgrade.20

Next time: Can Joan shake the ghost of fiancées past? Will it ever be possible to search “Allister McCormick” without turning up hits for “ + Mary Baker”? And will Mary finally marry, or at least affect a Serbian accent?

“Report Says Mary Has Married Allister,” Journal Gazette, August 19, 1922.

“Miss Mary Landon Baker Has Decided to Wed Mr. McCormick,” Greensboro Daily News, August 26, 1922.

“‘Contrary’ Mary Again Postpones Wedding Bells,” Nevada Daily Mail, September 15, 1922.

“Procrastinating Mary Lingering in London,” Cosmopolitan News Service/Rochester Evening Journal, September 16, 1922.

“Mary Landon Baker to Return Unwed,” Aurora Daily Star, December 16, 1922.

“Who’s to Wed Mary Baker? Don’t Ask Dad—Doesn’t Know,” Baltimore Sun, January 7, 1923.

“‘I’m Going to Be an Old Maid,’ Says Mary Landon Baker, Reviving Gossip,” New Castle News, January 20, 1923

“Mary Returns With London Accent as Thick as Fog, Suitor to Match,” Star Tribune, February 14, 1923.

“Mary Baker to Forsake Sensations,” Los Angeles Times, April 11, 1923.

Debutante, “Hopeless Love Back of Mary Landon Baker’s Indecisions,” Daily News, May 20, 1923.

“Allister McCormick to Wed Joan Stevens,” Santa Rosa Republican, August 31, 1923.

“A. M’Cormick Wed to Joan T. Stevens,” New York Times, October 6, 1923.

“M’Cormick Civil Wedding Quietly Observed in Paris,” Associated Press/Evening Independent, October 5, 1923.

The more proper rendering of his name is “Božidar Purić,” but for the sake of consistency and harmonization with the 1920s sources, the bastardized English newspaper spelling will be utilized.

“Mrs. Allister McCormick Tired Of Mary Baker Talk,” Baltimore Sun, June 1, 1924.

“Ghost of Buried Romance Annoys Mrs. M’Cormick,” Daily News, June 1, 1924.

“Twice Truant Bride of McCormick Subject for Wedding Rumor Again,” Associated Press/Evening Independent, November 5, 1925.

“Mary Landon Baker Nenies Nuptial Aims,” International News Service/Telegraph-Herald, January 25, 1926.

“Mary Landon Baker Has Even Her Dad Guessing This Time,” Associated Press/Atlanta Constitution, August 5, 1926.

“Mary Landon Baker is Again Reported Engaged to Wed,” Evening Review, October 5, 1926.