“Dainty” is a medieval sort of term, deriving from the circa thirteenth century “deinte” and its French predecessor, “deintie,” both initially suggesting ideas like elegance, luxury, and regard. Within about a century, its meaning had shifted to the more familiar sense of “delicately pretty” or otherwise exquisite in “taste or skill,” along with the more biting notion of excessive pickiness and delicacy. Shakespeare was fond of the word in all its potential colors, it was used somewhat ironically in the bawdy seventeenth century Scottish folk tune “Dainty Davie,” and it maintained a reasonably common place in literature in the subsequent centuries, featuring often in the works of authors like Elizabeth Gaskell and Charles Dickens (including a sneering “I dare say the boy isn’t too dainty to eat ‘em?” in Oliver Twist).

And so it continued in everyday parlance, appearing often as a food-related term—see cookbooks like Dainty Dishes, Receipts (1866), Cooling Cups and Dainty Drinks (1869), and The Dictionary of Dainty Breakfasts (1899)—and sometimes in reference to women’s fashion. Today, when it appears, it’s typically used to describe an aesthetic. Merriam-Webster online, for example, which provides recent example sentences for any word it defines, cites almost exclusively fashion and design-related usages, along with one tongue-in-cheek observation about what one particular male celebrity is not.

Google’s Ngram Viewer, a convenient tool that analyzes texts available on Google Books to plot a given word or phrase’s popularity in print over time, suggests that the modern heyday of “dainty” occurred in the late 1890s, after which the word declined rather steeply, before experiencing a minor revival from the late 1910s through the 1920s. After 1925, its retreat into near obsolescence began—and likely for its own good.

A lengthy 1903 The Cosmopolitan article on “Grace in Woman’s Costume” includes a paragraph on the critical quality of daintiness—a now explicitly feminine characteristic.

Moreover, grace is likely to carry with it an instinctive daintiness—another quality manly men lack, themselves, but admire in women. Daintiness in the selection of material, in the wearing of a gown, in the arrangement of the hair, in everything external is dictated by a daintiness of mind which is still more attractive. A frowsy looking woman usually has a frowsy mind. Her desk is in confusion. Her purse, she is sure, is in the bureau-drawer, or behind the picture on the piano, or down-stairs in the lower hall. The woman of grace and daintiness may, on occasion, demand great sacrifices from her husband; but she will never try to train him to hunt trifles and lead a life of fetch and carry.1

1902 saw the arrival of the Dorothy Dainty children’s book series by Amy Brooks, focusing on the adventures of a wealthy only child. And while copywriters and magazine articles in this period would also apply daintiness to items like breakfast cereal and neckwear, the term continued to pick up steam as a matter of personal virtue, as seen in 1908’s “The Busy Girl,” an essay on “the girl who sheds daintiness”

The first requisite for the girl who would be dainty is immaculateness, and surely this is attainable by any girl with a note of personal pride in her make-up. Collars, belts and shoes are the finishing touches to a girl’s toilet and may be stretched wonderfully in solving the problem of daintiness.

[....]

I think however, a girl’s shoes are strong factors in settling the question of daintiness. If you want to be attractively shod you must keep on hand at least four pairs. [...] If girls only realized how important a part in their lives the question of their daintiness plays, more would strive for the coveted grace. I know a business man who engaged his stenographer not knowing anything about her ability to work, but judging because she was particular in little things of personal appearance that she would be as conscientious in her business life.2

An enlightening takeaway here is that even in the Edwardian period, daintiness was clearly not intended to be synonymous with domesticity and motherhood, the traditional hallmarks of proper femininity. Indeed, even the most liberated professional woman could be dainty.

Daintiness could also be used as a near-synonym for cleanliness and sanitation, as suggested by this advice in How to Train Children from the same year:

Without inculcating selfishness, and in connection with daintiness of habit, should come lessons in the pride of possession. [...] If there be ten children, there should be ten brushes and ten combs, ten wash-clothes and ten towels—and—ten toothbrushes. This last may seem almost too ridiculous to mention, but, though rare, fortunately, there are households where there is something in the bath-room, which is known as “the children’s tooth-brush.” [...] All these things should be individual possessions for three reasons, personal daintiness, sanitation, and character building.3

Over the next decade, daintiness continued its new multi-purpose mission. While its relevance to food and fashion remained (beef bouillon cubes, marshmallow sauce, and lingerie all deemed embodiments of daintiness), it was also used to advertise Sanitol toothpaste, the best way for the lady of 1912 to remain “exquisitely dainty.” The Ladies’ Home Journal of 1914 presented a veritable smorgasbord of daintiness: used in January to describe undergarments; February slippers; April children’s clothing and the mothers who sew it; May women’s shoes, dress shields, and deodorant; June baking powder, muslin curtains, and deodorant; July newborn babies, dimity cotton, and (again) dress shields and deodorant; August Hormel’s Dairy Brand Hams and Bacon (“purity in the highest, with daintiness and ‘keeping’ quality supreme”); November slippers and glassware for tea services; and, to close out the year, one last hurrah for Comfy brand slippers.

Small wonder that within the next few years, as war raged in Europe, daintiness in the US went meta, with companies seeking to capitalize on the increasingly potent quality and advertisers—members of a swiftly professionalizing field—rushing in to help. Walden’s Stationer and Printer in 1915 recommended Des Arts Dainty Greeting Cards to its trade audience. “The name Des Arts has come to be a synonym for daintiness in cards and stationery in a very few years,” the writer observed. “Wherever flat printing is used, it is invariably from zinc plates, and with a daintiness of line and design which characterizes Des Arts productions.” In another spot, found in a 1916 issue of Dry Goods Economist, New York’s Fashion Camera Studios promoted photography’s advantage over illustration to, among other things, “suggest daintiness and distinction” as well as “portray strength and service.” In a later issue, clothing merchandisers were advised that “Daintiness Is the Keynote of This Season’s Merchandise.”

1919 seemed to be a last hurrah for dainty’s innocence, and home goods advertisers used it like it was going out of business. In Good Housekeeping alone, it appeared in spots for bassinets and crackers, Thermoses and Campbell’s soup (featuring the unusual adverbial phrase usage “prepared with utmost care and daintiness”), and articles about doilies; Women’s Home Companion added hat dye, home decor, and brassieres.

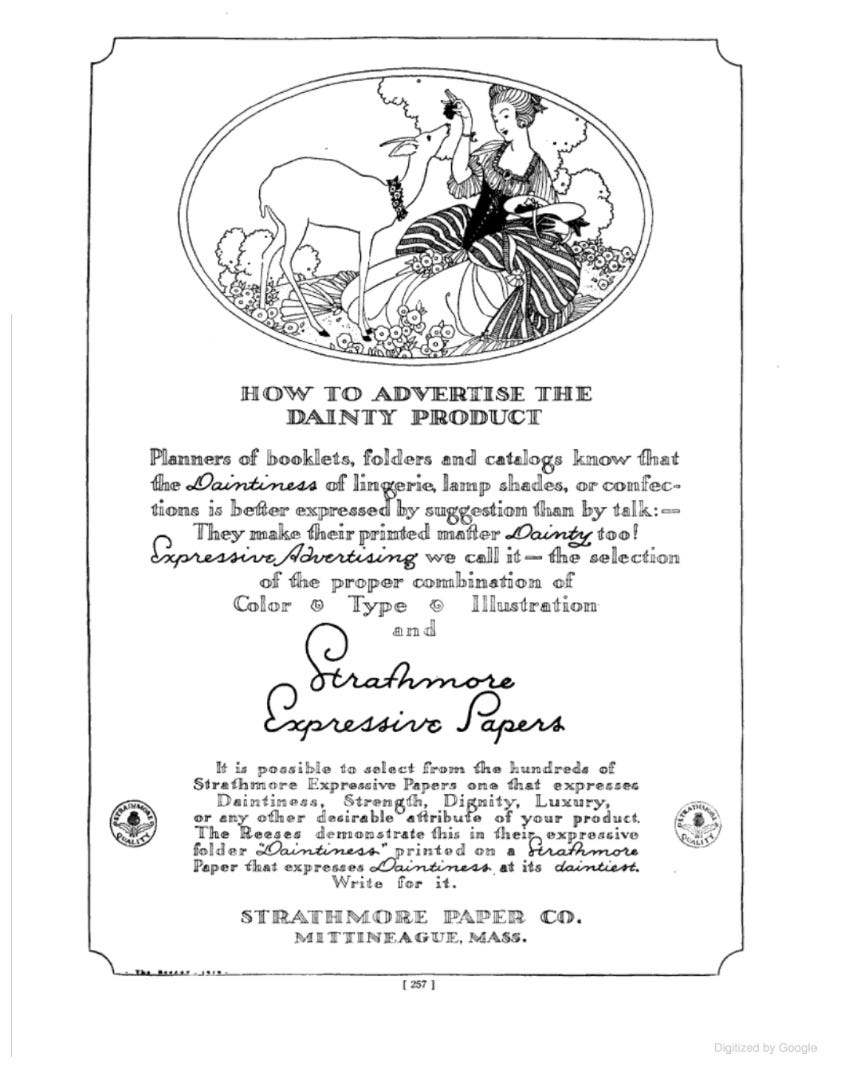

As the ‘20s dawned, businesses were promised new assistance in dainty selling from the likes of Strathmore Paper Company and its Expressive Papers, while photographers could learn from The Camera how to ensure daintiness of image composition. The daintiest typeface? Goudy Italic, of course, as Printing Type Specimens informed printers and advertisers in 1924. But while 1922’s Boot and Shoe Recorder remained committed to the daintiness of children’s footwear, advertisers had, as if in concert, settled on a singular connotation.

Daintiness was purity. And, more than purity, a specifically feminine sort of purity. Throughout the 1920s, “dainty” became a hygiene-specific buzzword. Deodo, a deodorant powder recommended for use in both armpits and sanitary napkins, guaranteed (in Strathmore-friendly script font) “The unfailing charm of daintiness” when using the product daily. “How dainty!” observes a woman, in script-fonted voice, in an ad for Guest Ivory soap, a product clad in “blue dress to symbolize purity”—a most intriguing instance of making the subtext text.

Odorono, “the liquid corrective for excessive perspiration,” reminded women that “there is one quality which men expect, always, in a woman—personal daintiness!” and, in another ad, used the word three times in its first five sentences. “The dainty woman does not KEEP corns,” admonished Blue=jay Corn Plasters, while Manon Lescaut face powder promised “Daintiness joined to joyous fragrance.” Displacing the previous decade’s Sanitol as leader in this specialization, Pepsodent was now the toothpaste “For Dainty People—For Beauty Lovers.” Even English soap and perfume brand Erasmic recommended its product “For Daintiness & Refinement.”

Especially disturbing, Lysol joined the campaign, using the most coded of language to remind women that their “three requisites are health, youth—daintiness” and recommending its product as a “health and daintiness precaution.” Marvel Hygienic Spray explicitly linked “personal daintiness” with “feminine hygiene” and gynecological advice. For advertisers who needed to exercise discretion, and the consumers who expected it, this was a most useful euphemism, and Kotex, pioneers of a new disposable menstrual pad, gladly availed of it.4 The product could allow women to “insure poise in the daintiest frocks,” claimed one early 1921 ad, and the debutante of 1925 could feel equally comfortable in the “filmiest of gowns.” Kotex could resolve the “fear of lost daintiness.” By 1929, Kotex itself would not only protect the daintiness of one’s wardrobe, but actually represent the value. Why buy Kotex? “Because it’s Smart…Fastidious…Dainty.”

As the 1930s began, the term was plainly waning from its widespread usage even as a beauty and hygiene buzzword, but it continued to make critical cameo appearances. The siren of 1932 was “so dainty herself, you would expect her to rely on the purity of genuine Kotex.” Depending on how highly she values her daintiness, she might also rely on Lifebuoy Health Soap, while by 1937 preferring Mavis Talc to “safeguar[d] feminine daintiness.” Still, it was becoming clear that daintiness was no longer the critical virtue of the mid-twentieth century woman, and as the daughters and granddaughters of the dainty generation came of age in the post-World War II era, the term seemed about as au courant as the name Gertrude.

And so “dainty” was doomed by its own practicality; so efficient as a euphemism that it would take years to become detached from the idea of cleanliness and feminine hygiene, so euphemistic that it would appear old-fashioned to women of a later, franker era. Today, the word has mostly reclaimed its earlier sense, conjuring images of delicate necklaces or the wispiest of individuals. But its reign in advertising is unlikely to be restored.

Hjalmar Hjorth Boyesen II, “Grace in Woman’s Costume,” The Cosmopolitan, Vol. XXXIV, No. 6, April 1903.

Mame B. Griffith, “The Busy Girl,” American Motherhood, Vol. XXVII, No. 2, August 1908.

Emma Churchman Hewitt, How to Train Children, Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Company, 1908.

The company did, though, enjoy changing things up; a number of ads from the mid to late ‘20s promise instead “charm,” “exquisiteness,” or “immaculacy.”