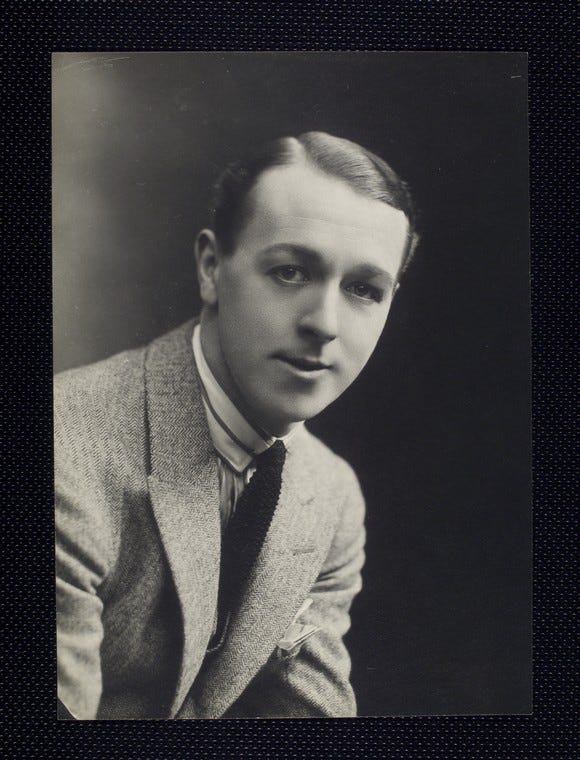

Barry Baxter today appears to be mostly notable for two things: his death at the young age of 27, and his enduring good looks and taste in dogs.

But even in his own day, Baxter’s celebrity was limited. His New York Times obituary highlighted work in the musical comedy The Cinema Star, retitled The Queen of the Movies for its American run, and the play Happy-Go-Lucky, and spent an equal amount of space on his stint in the British transport service during World War I, which within a year resulted in 18 months of hospital convalescence.1 He appeared twice in a register of The Best Plays of 1921–22, first in a cast list for the comedy Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife, in which he played “Albert De Marceau,” and then, sadly, in the book’s Necrology, a roster of all theater personalities who had passed between the Junes 15th 1921 and ’22.2

So it’s less than surprising, probably, that the major story surrounding Baxter’s premature demise was its impact on the Baker and McCormick affair. Indeed, many fresh tidbits emerged, such as the revelation from one party that Mary and the actor were introduced by “Lord Allington”—possibly Napier Sturt, 3rd Baron Alington, best known for dating actress Tallulah Bankhead—and a report from the New York Times that Baxter

was a close friend of both of the principals in that romance, and both before and after the postponement of the marriage between the two he was consulted by them and often seen in their company.3

But the Chicago Tribune’s report of the latest delay dismissed Allister’s friendship, and instead noted that the “handsome” Baxter “was with Miss Baker frequently at the time she failed to appear for the church wedding after her return from California, where she went to regain her poise.”

The Tribune—published at that time, coincidentally, by Allister’s cousin Robert R. McCormick—held little back in its consideration of Baxter’s role as an “almost invariabl[e]” third party to Mary and Allister’s public activities. In addition to citing the rumored “wedding dress” telegram, it included some new gossip. “Among Miss Baker’s friends,” confided the reporter, “Baxter was regarded as a suitor whose love for her was quite as ardent as that of young McCormick. Both she and Baxter found it necessary to deny stories of a secret wedding, Baxter adding that he already had a wife.”4

If Baxter truly possessed a wife, and not just a poor instinct for PR spin, she was vanished by May 1922; he is said to have been survived by an ailing father, “an invalid mother, a brother and a sister, all in England.”5

Within a day of the scandal’s break, damage control arrived via a response in the New York Times from Dr. E.L. Rounds, the “woman physician” at whose home Baxter had died. Her “emphatic denial” of any entanglement between Baxter and Baker beyond friendship included criticism of the media for some unsurprisingly poor editorial judgment. “There is nothing to it at all,” she said. “Why, one newspaper that was so positive in printing this erroneous report even published a picture of Mr. Baxter that wasn’t his picture at all.”

It’s a special sort of fitting, then, that the same article, citing Baxter’s cause of death as pneumonia, cheerfully attributed its emergence—manifested when he fainted after a play—to one thing only: “At the time of the collapse reports were circulated that his ill health might be connected with Miss Baker’s decision to go to London to marry Mr. McCormick, after several postponements of the nuptials.”6

While the saga helped inspire an exciting full-page spread in one tabloid about “Jilting—the Latest Indoor Sport of Society Buds” (a piece which also introduced the decades-ahead-of-its time phrase “pulled a Mary Landon Baker”)7, the unseemliness surrounding Baxter’s death, coupled with the limbo of inconclusive wedding arrangements, left the actual Baker/McCormick saga to die down for an uncharacteristic two or so weeks. But in early June, the International News Service (INS) caught wind of Mary’s plans to journey from Paris to London, leaving Allister—who at some confused point had elected to remain in France—bereft.

Though Illinois’s Journal Gazette reported a rumor that Mary had told a Chicago friend her plans to break ties with Allister and return to the States,8 INS correspondent Frank E. Mason elected to set the record straight. Inspired by the sensitive literary stylings of peers like Patricia Daugherty, Mason took special note of Mary’s single goodbye kiss for her “young Chicago millionaire” fiancé before departing for England with her mother. “[McCormick] was visibly affected by the leave taking,” he noted. “In true sweetheart fashion the young millionaire remained on the train bidding an affectionate farewell until it began to leave the station.”

Allister shared a few parting words, channeled through Mason’s romantic novella. “She is gone and I won’t see her for a week,” he “murmured,” eyes welling with tears while Mary “fidgeted” and “lingered” before returning to the train’s platform for the climactic moment:

“Promise me you will not forget me while you are in London,” urged Allister.

Miss Baker replied in a low voice, but the answer evidently was satisfactory.9

After bemoaning the tedium of a Mary-less Paris, Allister assured his audience that the wedding would occur in autumn—a point that Mary, one day later, would dispute in a statement to the International News Service, prompted by her weariness with interviews.

“My marriage will take place within two or three weeks in a funny little English country place—Weybridge—and it will be the quietest thing ever seen in England,” said Miss Baker. “I am keeping everything secret. Only my mother and myself know the date. We are taking great precautions to prevent newspapers from knowing it.”10

Allister quickly vouched for the new arrangement, the unnamed reporter this time guaranteeing “no chance” of a repeat failure.11

The affair settled, it was, naturally, time for an elaborate front-page Sunday edition feature piece recapping the European adventure.

Paris loves a romance. If there is a hint of mystery so much the better. A triangle is preferred. An octagonal would be still more deeply appreciated.

There’s an old saying, “When a woman will, she will, and when she won’t, she won’t, and that’s an end on’t.”

But the adage doesn’t apply to Miss Mary Landon Baker, the “nervous bride-to-be,” pretty Chicago girl, who changes her mind about her marriage to Allister McCormick almost as often as her gowns. And she has eight trunks full of gowns.

There’s little in the way of news on offer—Mary was spotted late at night at a Parisian dance club in the company of two unidentified young men; her rebellious spirit extended to sporting short skirts, an American trend that was sadly out of fashion in her French milieu. Mary is also quoted, attributing the repeated delays to doctor’s orders—her “nervousness” making a wedding’s excitement inadvisable—and “complications,” not including the death of Baxter to what here would seem to have been the consequences of an untreated head injury. Despite Paris’s apparent thrill for the amorous intrigues of two twentysomething members of the Chicago and London society sets, the article suggests just the slightest air of fatigue. “May has passed, June is well underway, but still no wedding bells,” concludes the feature. “Baxter’s death lent a touch of tragedy to what was jointly comedy and romance.”12

And by June 18, Mary would become the centerpiece of another extended report, this one run in the Philadelphia Public Ledger:

What would you do if the girl you loved and wanted with all your heart had turned you down three times, once at the very altar?

That is what pretty Mary Landon Baker has done to young Allister H. McCormick. The Chicago heiress has gone back on her word once more, and now announces that the wedding set “surely and positively” for London in May, “or perhaps June,” has been postponed until September. Allister is still trailing along, doing his best to win his elusive bride.

The unidentified journalist behind this latest piece, told in sections marked off with emphatically bolded titles like “‘Made for’ Allister,” shared many previously undisclosed tidbits:

Mary is aesthetic. She writes epigrams every day, just after breakfast. Once, in greeting an interviewer, she said: “I’m so glad you’ve called. I’ve just dashed off a few epigrams.”

Here they are:

“We are all clowns in the dusty arena of everyday life; fate is our ring master.”

“As sleep at night is intolerably ridiculous, so is work in the daytime.”

“Solution is like a drug. A little of it quiets the turmoil of the brain, but too much deadens the nerves.”

Indeed, in 1920 Mary had published Verbum sapienti, a collection of heady morsels of wisdom like “Visions are incorporeal cinematographs” and “Time and space are material hallucinations.”13 (It’s worth considering the success Mary could have had on Instagram a century later.) The author here, however, is more concerned with an unnamed, and likely unpublished, roman à clef that featured poorly disguised stand-ins for her society compatriots:

[N]obody had any difficulty whatever in picking out who was who. The painful part about it was that she showed in the book that she considered everybody in society except herself had a head of solid ivory. So, of course, she was the only person who read the book who really liked it.

But Allister treasured his whimsical fiancée: “She was made for him, he murmurs to his friends. She has a great brain, he is convinced.” For Mary, love was a fresh epigram:

“Remember, a perfect love never loves. Isn’t that expressive?”

“Sure. But what does it mean?”

“Just what it says,” she explained. “And remember this, too. A woman should only listen to the tiny urge of a personal destiny, called by the grouping multitude, intuition.”

“Well?” she was asked.

“Well,” she concluded, “a wise girl should obey hunches at all times, and I always will.”14

This shift in tone—less amusement and intrigue, more irritable sympathy for a wronged man and resentment towards his errant bride—was no outlier. Indeed, the storyline had entered a new but inevitable phase—tearing Mary apart for her once-entertaining idiosyncrasies. And unfortunately for Mary, those very foibles would ensure this feature proved timely; within three days came report from the United Press that Mary—now dubbed the “phantom bride”—remained ambivalent about the arrangements. “‘Contrary Mary,’ declared the piece, “now says she will return to the United States Sept. 1 and that if the nuptials are not celebrated before that date, they never will be.” This article endeavored to analyze the causes of Mary’s changeability:

According to her close friends, she is easily influenced, sometimes taking the advice of her mother, who opposes the marriage, and at other times following the lead of the McCormick family, which is urging a quick wedding.

She is traveling with her mother, and by day is under her influence, according to this version, and taking tea, dancing and going to suppers with McCormick, at which times she is ready to marry him.15

A full-page Sunday spread just one week after the Public Ledger’s hit was less a feature or report than a one-star human review, arguing the point that Allister—“a thoroughly wholesome, nice chap and very rich”—may certainly be luckier not to wed Mary. “What is the matter with Mary Landon Baker?” wondered the intrepid critic.

Is she a spoiled child who cannot see what a cruel thing it is to play hide-and-seek with a man’s heart?

Is Mary a perfectly heartless girl, governed by utterly selfish whims, who does not care how wretched she makes the man who loves her?

Or is Mary Landon Baker such an unstable, volatile little person that she really does not know her own mind from one hour to another and is deeply in love with Allister McCormick one day and indifferent to him the next?

Is such a girl worth marrying?

The author predicted that Mary’s whims foretold “interminable misery” for any future husband, and credited her with this bombshell:

I shall naturally meet many young eligible men in the English social world. If there is anyone I feel I like better than I do Allister, I shall break my engagement. If I do not meet anyone I like better I shall return to France, probably in September. And then my marriage to Allister will be quietly celebrated.16

Mary even became fodder for doggerel later that summer, featuring in a July 21 installment of playwright Bide Dudley’s syndicated “Good Evening!” column:

Miss Mary Landon Baker,

As sure as you are born,

Is sayin’ she’ll be married

On some September morn

The news is so exciting

It’s causing quite a buzz.

Yep, Mary says she’ll wed him;

We’re praying that she does.17

It was clear the story was beginning to run on fumes. A marriage might open some new doors—reports of exotic outings with other society couples, the innocent speculative fun surrounding a child’s birth, and, of course, sordid rumors of extramarital liaison—but the whimpered ending of a breakup grew more probable by the week.

Next time: Will Mary meet her fancy young eligible Englishman? What is Allister’s plan B? Where is the screwball comedy featuring wacky interludes of reporters climbing through Mary’s hotel room window, or at least a jaunty 1920s Verbum sapienti novelty tune?

“Barry Baxter Dies After a Collapse,” New York Times, May 27, 1922.

Mantle, Burns, ed. The Best Plays of 1921–22. Boston: Small, Maynard & Company, 1922.

“Barry Baxter Dies After a Collapse.”

“Love, Tragedy Tangle Seen in Baker Nuptials,” Chicago Tribune, May 28, 1922.

“Barry Baxter Dies After a Collapse.”

“Denies Actor Loved Mary Landon Baker,” New York Times, May 29, 1922.

“Jilting—the Latest Indoor Sport of Society Buds,” The Morning Tulsa Daily World, June 4, 1922.

“Mary Landon Baker is Soon to Sail for Home,” Journal Gazette, June 8, 1922.

Mason, Frank E. “Mary Landon Baker Leaves for London and M’Cormick Will Follow in Few Days,” International News Service/Pittsburgh Press, June 8, 1922.

“Miss Baker Will Be June Bride, Says So Herself,” International News Service/Pittsburgh Press, June 9, 1922.

“To Avoid Dramatic,” Border Cities Star, June 10, 1922.

“Paris Asks Will M’Cormick Ever Lead Miss Mary Landon Baker to Marriage Altar and If So, When,” Charleston Daily Mail, June 11, 1922.

Baker, Mary Landon. Verbum sapienti. Chicago: Ralph Fletcher Seymour, 1920.

“Ideal Lover Never Loves,” Philadelphia Public Ledger, June 18, 1922.

“‘Contrary Mary’ to Be Married by Fall or Never, Is Latest,” United Press/Pittsburgh Press, June 21, 1922.

“Four Times ‘Left Waiting at the Church,’” Washington Times, June 25, 1922.

Dudley, Bide. “Good Evening!,” The Evening World, July 21, 1922.